Millions of malicious activities and cybersecurity-related responses occur daily in the information communication technologies (ICT) environment. While it is impossible to provide an exact figure, efforts to assess daily activity in the ICT environment estimate that around 600 million cyberattacks occur each day. For each offensive activity spotted, there is a corresponding defensive response triggered by its very detection.

The number of malicious ICT activities is on the rise, and both the private sector and the international community have expressed preoccupation with this trend. In particular, Member States reiterated in a recent progress report of the Open-Ended Working Group on security of and in the use of ICTs 2021–2025, increasing concern that ICT threats in the international security context have intensified and evolved significantly in the current geopolitical environment.

The international community and non-technical stakeholders often face several challenges in understanding malicious ICT activities, either due to the complex language used by the technical community or the frequently simplistic language used by media to portray ICT incidents. To help Member States, UNIDIR has produced a new framework for analyzing ICT activities: The UNIDIR Intrusion Path.

Understanding the complexities of ICT threats

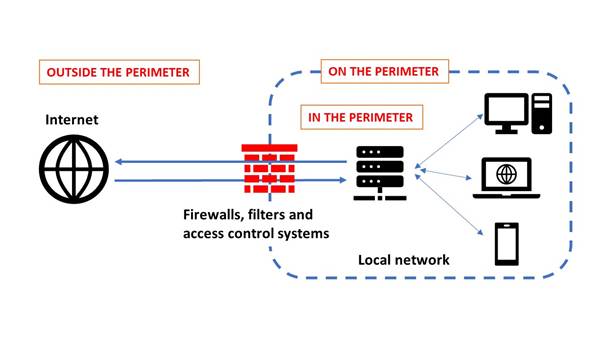

The UNIDIR Intrusion Path is an accessible framework to analyze both malicious and security activities in the ICT environment. It is built around the concept of the network perimeter, which categorizes the ICT environment into the dichotomy of outside and inside according to an organization’s network. Thanks to this ‘spatial’ understanding of the ICT environment, it aims to help visualize the different layers where ICT activities can take place, thus offering a tool to make cyber diplomacy more inclusive and better informed.

In general terms, a ‘network perimeter’ refers to those systems that delimit a specific network from the broader Internet, mostly by managing security of and access to internal networks (see fig. 1).

Figure 1. Simplified overview of a network perimeter

This understanding creates three key layers of analysis – outside the perimeter, on the perimeter and inside the perimeter.[1]

- Outside the perimeter encompasses all the systems, networks and data sources that exist beyond an organization’s direct control (e.g., public databases and repositories,[2] social media and public websites, dark web, and cybercriminal forums[3]).

- On the perimeter represents the boundary between an organization’s internal systems and the external world. This boundary is protected by layers of security meant to filter, monitor and control access (e.g., firewalls and intrusion detection or prevention systems[4]).

- Inside the perimeter is the internal, private part of an organization’s network. It is often characterized by a series of segmented and monitored subnetworks and devices that house sensitive data and operational systems (e.g., data servers and file repositories, desktop computers, mobile devices, and other equipment).

For each of these layers, there are specific actions that perpetrators (i.e., the attackers) seeking to penetrate and those in charge of the security of the network (i.e., the defenders) must conduct. Perpetrators need to find out how to breach the system defences and achieve their goals, while defenders need to monitor and deter any unwanted and unauthorized intrusion. There are several ways of categorizing the different actions that these actors should take. The most famous are the Cyber Kill Chain and the MITRE ATT&CK.

Complementarity with existing models and practical use

The Cyber Kill Chain, developed by Lockheed Martin, is a model that outlines different stages of a cyberattack, from initial reconnaissance to data exfiltration. It consists of seven sequential phases: reconnaissance, weaponization, delivery, exploitation, installation, command and control, and actions on objectives. The purpose of the model is to help defenders to detect, prevent and respond to intrusion attempts by identifying and disrupting adversarial actions at each stage of the chain. It is particularly useful in understanding how attacks operate and where defensive measures can be most effectively applied. The Kill Chain presents intrusion as a linear and temporal progression through seven stages, yet often real-world malicious activities involve non-linear, iterative, or parallel tactics that may not properly fit into this model.

The MITRE ATT&CK framework was developed and is maintained by MITRE Corporation as part of a research project to understand adversary behaviours better and to improve defences against cyber attacks through real-world, evidence-based models. It categorizes the tactics, techniques and procedures used by perpetrators across different stages of an intrusion. Unlike linear models, ATT&CK presents a matrix that maps specific techniques to broader tactical goals, such as initial access, privilege escalation, or data exfiltration. While the MITRE ATT&CK framework is a powerful tool for understanding adversary behaviour, it has some limitations, including its complexity and technical depth, which can make it difficult to use effectively without suitable knowledge and training.

The UNIDIR Intrusion Path model builds on and complements these two well-established tools for analyzing malicious ICT activities. In fact, its elements are compatible with and can include both the Cyber Kill Chain and the MITRE ATT&CK categorizations (see table 1).

| UNIDIR Intrusion Path layers | Cyber Kill Chain steps | MITRE ATT&CK tactics |

| Outside the perimeter | Reconnaissance Weaponization | Reconnaissance Resource Development |

| On the perimeter | Delivery Exploitation Installation | Initial access Execution Persistence |

| Inside the perimeter | Command and control Actions on objectives | Privilege escalation Avoid detection Credential access Discovery Lateral movement collection Command and control Exfiltration Impact |

Moreover, the UNIDIR Intrusion Path builds on already existing intrusion frameworks in terms of what activities both the perpetrators and the defenders might do in their respective roles. Considering that these activities may involve highly technical skills and knowledge, the UNIDIR Intrusion Path provides a simplified summary of what both perpetrators and defenders can do in each layer of the model.

| The UNIDIR Intrusion Path | ||

| Layers | Perpetrators | Defenders |

| OUTSIDE the perimeter | The perpetrator gathers information on the victim that can be used to prepare the malicious ICT act (e.g., emails, network characteristics, vulnerabilities). Then, the perpetrator uses this information to prepare the resources to begin the intrusion, which consists of coupling malware with a vulnerability in the perimeter to create a payload to be used during the intrusion. | Defenders search for signs of malicious activities through different methods, including browsing vulnerability repositories, collecting server logs and seeking to identify reconnaissance behaviour. |

| ON the perimeter | The perpetrator attempts to penetrate the victim’s system. The intrusion begins with the delivery of malware (e.g., through a phishing email or supply chain compromise) and the execution of exploits for the perimeter vulnerabilities identified in the previous phase. Once the perimeter is compromised, perpetrators must maintain access to the system. | Defenders must secure the perimeter and avoid intrusion. They can rely on active or passive defensive measures, both of which are augmented by information gathered outside the perimeter. |

| INSIDE the perimeter | The perpetrator penetrates the network and establishes command and control of the compromised system. The perpetrator can now carry out several actions according to their objectives. | Defenders must identify and block a perpetrator’s command and control and rapidly detect and disrupt the perpetrator’s actions to limit the impact of the intrusion. |

The UNIDIR Intrusion Path model has already been used in a research project aimed at understanding how artificial intelligence (AI) is changing the capabilities and behaviours of both perpetrators and defenders throughout the different layers of the intrusion path.

As malicious activities in the ICT environment increase and pose growing threats to international peace and stability, it is essential to equip policymakers, practitioners and other stakeholders with tools to understand, inform and act for a more transparent, stable and peaceful digital space. We hope that the UNIDIR Intrusion Path will contribute to this end.

[1] Note on ‘cloud’ resources: virtual or remote resources are integral to modern networks, often spanning both outside and on the perimeter. External services like public cloud platforms typically fall outside the perimeter, requiring robust policies for access and configuration security. In contrast, organization-controlled cloud infrastructure, such as hybrid clouds or cloud-hosted applications, functions on the perimeter, serving as critical access points and potential vulnerabilities. As extensions of the network, cloud resources demand tailored security strategies and shared accountability with providers. While this is an important topic, a detailed discussion of the security of cloud resources is outside the scope of this paper.

[2] These may store information on potential vulnerabilities, system configurations and employee profiles.

[3] Information on new exploits, vulnerabilities, or prepackaged intrusion tools can be found in such spaces.

[4] These are stationed at the network’s edge (as well as at other parts of the network) to monitor, filter and block malicious traffic.