Last November, the fifth session of the Conference on the Establishment of a Middle East Zone Free of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction (ME WMDFZ) coincided with Saudi Arabia rescinding its Small Quantities Protocol (SQP) to its Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement (CSA) with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). This shift was motivated by the country’s decision to increase the role of nuclear energy in its energy mix strategy. The discussion at the conference regarding the commitments for minimum safeguards that should be adopted to verify a future ME WMDFZ, coupled with the growing interest in the region to pursue peaceful nuclear applications, warrants a renewed examination of the status and potential limitations of the SQP in the Middle East.

What is the Small Quantities Protocol?

Many Non-Nuclear-Weapon States parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons that have small amounts of nuclear material, but have no nuclear material in facilities, have concluded SQPs with the IAEA. An SQP is not a stand-alone agreement; rather, it is an addition to the standard CSA (based on INFCIRC/153) that suspends the implementation of certain safeguards procedures in Part II of the main agreement.

Although SQPs were designed to reduce the burden on the IAEA and on States with no significant nuclear programme, they limit the Agency’s ability to receive initial declarations on nuclear material subject to safeguards (based on the original SQPs) and to conduct routine inspections in such States (under both the original and revised SQPs). Consequently, they reduce the IAEA’s ability to verify those States’ nuclear activities.

The IAEA General Conference has repeatedly adopted a resolution reaffirming “the urgent need for all States in the Middle East to forthwith accept the application of full-scope Agency safeguards to all their nuclear activities as an important confidence-building measure among all States in the region”. States in the region have tabled this annual resolution and emphasized the confidence-building role of CSAs because their application enables the Agency to verify a State’s nuclear activities to ensure its peaceful nature and to raise the alarm if it detects signs of possible non-compliance.

The evolution of the protocol

The original SQP text was developed in 1974. Under this now-outdated model, a State qualified for an SQP if it had no nuclear material in a nuclear facility (as defined in paragraph 106 of the CSA) and the total quantities of nuclear material in the State were below the thresholds defined in paragraph 37 of the CSA.[1] Under the 1974 version of the SQP, the implementation of most reporting and all inspection procedures in Part II of the CSA are suspended – or “held in abeyance” – for the State concerned as long as it meets the two eligibility criteria or until it rescinds its SQP.

If either of the two criteria ceases to apply – that is, if the quantities of nuclear material exceed the set limitation or if nuclear material is moved into a nuclear facility – then the SQP ceases to be operational. The suspended safeguards procedures include those that require the State to make an initial report of all its nuclear material and those related to inspections and to design information verification (in which the IAEA verifies that a facility corresponds with design information submitted to the Agency). This means that the IAEA cannot verify nuclear material or facilities in a State with an original SQP, for as long as the State still qualifies for the SQP.

These constraints on the Agency’s verification compounded the view that the original SQP is “a remaining weakness in the safeguards system”. These concerns prompted the IAEA to modify the eligibility criteria for the SQP, making it unavailable to a State that had decided to construct a nuclear facility. In his 2003 report to the Board of Governors of the IAEA, Mohamed ElBaradei, Director General of the Agency, proposed two options: to get rid of all SQPs or to modify existing and future SQPs. Under the first option, no new SQP based on the original text would be approved with States that had yet to conclude a CSA, and the IAEA would call on States with existing SQPs to rescind them. Under the second option, the eligibility criteria in the SQP would change, and the IAEA would call on those with an original SQP to amend or rescind it to meet the Agency’s concerns. Although, according to the Director General’s report, the Agency preferred the first option since it could treat all States with a CSA in force equally regarding reporting and inspections, the Board of Governors adopted the second option.

The modifications were adopted by the Board of Governors in 2005. Following the adoption of the revised SQP by the Board, the IAEA Director General sent letters to all States with operational SQPs based on the original standard text, calling on them to either amend their original SQP to align with the new model or rescind it.

There are three main distinctions between the original and revised SQPs:

- The revised SQP mandates the State to declare an initial inventory of all nuclear material, including zero inventory as appropriate, and allows the Agency to conduct ad hoc inspections to verify these declarations.

- Under the revised SQP, the IAEA may also carry out special inspections.

- A revised SQP ceases to be operational as soon as a State decides to construct or approve the construction of a nuclear facility. States are required to inform the Agency once they make such a decision. In contrast, under the original SQP, they were only under an obligation to do so six months before nuclear material is introduced into the new facility.

The protocol’s status in the Middle East

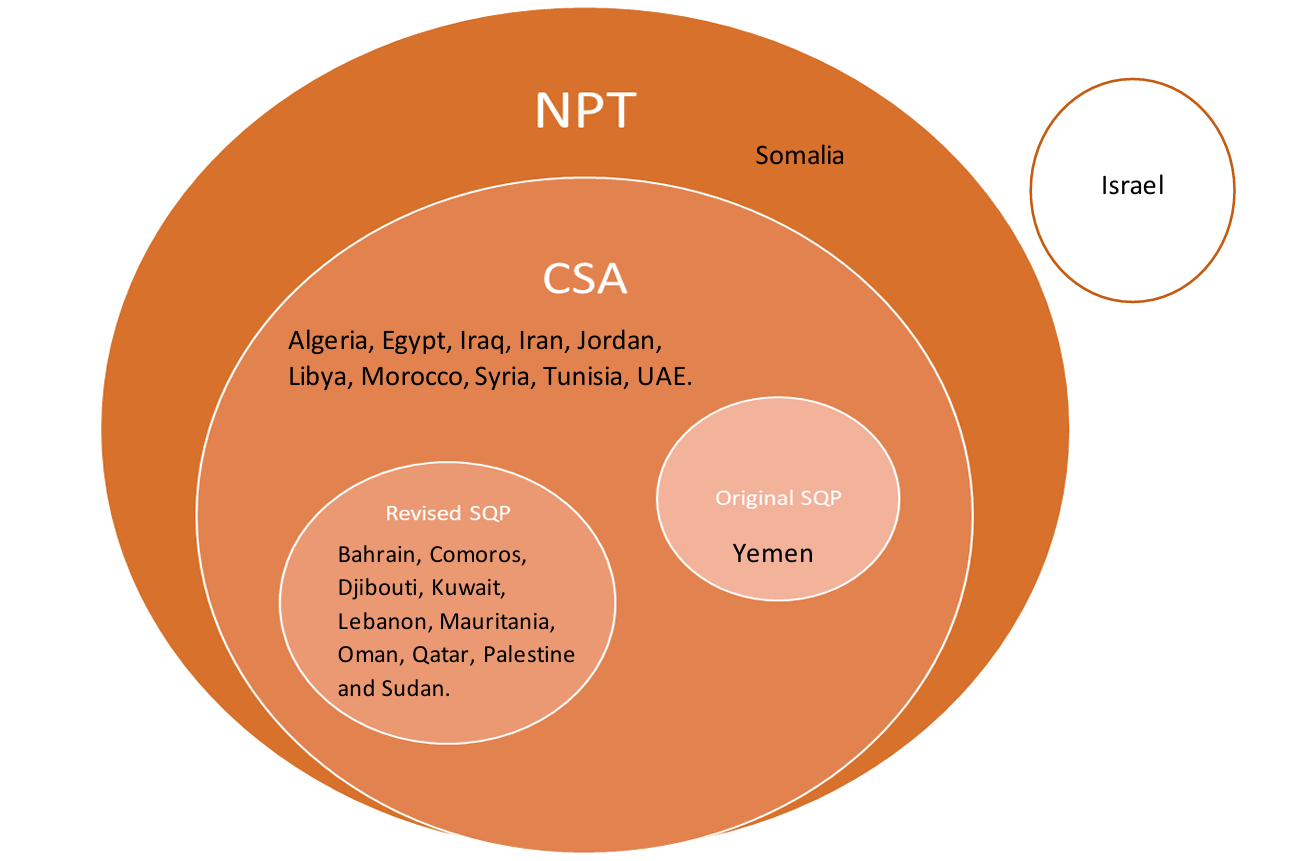

Eleven Middle Eastern countries have adopted SQPs, in addition to their CSAs with the IAEA: Bahrain, the Comoros, Djibouti, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritania, Oman, Qatar, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, and Yemen. All but one, Yemen, has adopted or updated their SQP to the revised version. The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia used to have SQPs, which they rescinded recently in 2019 and 2024, respectively (see Figure 1).

Since Israel is not party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, it does not have a CSA with the IAEA. Instead, it has agreed to an Item Specific Safeguards with the Agency, which apply only to the nuclear materials and facilities specified in the agreement, not all of the State’s nuclear activities. Somalia is yet to conclude a safeguards agreement with the IAEA.

Figure 1: Status of States in the Middle East in Relation to the Non-Proliferation Treaty and Related Agreements

The protocol’s limitations in the Middle East

The revised SQP significantly improves the IAEA’s ability to verify States’ declarations as it allows the Agency to conduct ad hoc and special inspections (see Table 1). However, no routine inspections may be conducted in a State with an original or modified SQP, unless and until the State either has nuclear material in a facility (under the original SQP) or decides to construct a facility (under the modified SQP) – in both cases, the SQP becomes non-operational.

| Inspection type | Purpose |

| Ad hoc (Paragraph 71 of CSA) | Verify the correctness of the initial report on all nuclear material subject to safeguards under the SQP that the state is required to provide to the Agency upon conclusion of a CSA and an SQP Verifying changes to the initial report Identify and verify nuclear material before transfer out of or into the state |

| Routine (Paragraph 72 of CSA) | Verify that a report received from a State to update the Agency on the status of inventory changes and material balance areas is consistent with the records that the State must keep based on its national system of accounting Verify the location, identity, quantity and composition of all nuclear material subject to safeguards Verify information on the possible causes of material becoming unaccounted for, shipper/receiver differences and uncertainties in the book inventory |

| Special (Paragraph 73) | Verify the information contained in the special report that a state should make in the event of a loss in the amount of nuclear material that exceeds the limit specified in the Subsidiary arrangement or change in the containment which violates the way it should be under the Subsidiary arrangement (paragraph 68) When the information obtained by the Agency through a State’s reports, clarifications or routine inspections is not enough for it to conclude the peaceful nature of the State’s nuclear activities |

Note:

- Subsidiary arrangements refer to a document specifying in detail how the procedures laid down in a safeguards agreement are to be applied. See IAEA, IAEA Safeguards Glossary, 14.

- Containment refers to the structural features of a facility, containers, or equipment that are used to maintain the continuity of knowledge of items by preventing undetected access to or movement of them. Complementary containment/surveillance measures usually ensure the continuing integrity of the containment. Ibid, 77.

Routine inspections constitute the majority of the Agency’s inspections at facilities and locations outside facilities. The intensity and frequency of routine inspections are specified in subsidiary arrangements. A State with an SQP is not required to bring subsidiary arrangements into force, as long as its SQP remains operational. By consistently receiving reports and conducting routine inspections to ensure that their content matches the reality of the State’s material inventory, the IAEA is aware of the State’s nuclear activities – an advantage that is not available under the original SQP (and to some degree the modified SQP).

Ad hoc inspections are carried out to verify a State’s initial declaration on nuclear material and any changes that arise or when material is imported into or exported from the State. A special inspection may be conducted as envisaged in the CSA, and it requires arrangements to be concluded between the State and the IAEA.

Considering the SQP’s limitation, the volatile conditions in the Middle East, the history of diversion, covert programmes, the past use of weapons of mass destruction, and the deep mistrust among the region’s States, discussions on the safeguards and verification standards of the future ME WMDFZ should consider which measures will offer regional States the most assurances related to compliance.

Considering minimum standards for safeguards

A future treaty on an ME WMDFZ will require assurances among Middle Eastern States regarding their compliance with their commitments to the treaty. To enhance this trust, States could discuss adopting a confidence-building measure within the framework of that treaty that aligns all of their nuclear non-proliferation commitments – based, at a minimum, on the CSA with none of the exceptions allowed by an SQP. As a first stage, those States that have not adopted a safeguards agreement will adopt, at the least, a CSA with the IAEA, and those that have a revised or original SQP will rescind it.

The advantage of such a measure is that the IAEA may then implement all safeguards procedures available under a CSA, such as conducting all types of inspections and design information verification, receiving routine reports, and monitoring compliance. It will assure all States in the region that they are unified in their obligations in relation to the Agency and that all nuclear materials and activities in the region – whether significant or not – are subject to the Agency’s scrutiny.

It should be acknowledged that fully implementing a CSA will incur some financial costs for the 11 States with an SQP, as it will require them to establish State institutions (including an authority responsible for safeguards) and recruit, train, and maintain qualified personnel. While paragraph 15 of the CSA outlines that the State is responsible for the costs associated with implementing the CSA, wealthier countries of the region could establish a fund to alleviate the financial burden on those countries that do not possess a significant nuclear programme and cannot afford to create the necessary support institutions and infrastructure.

[1] These thresholds are: (a) 1 kilogram in total of special fissionable material, which may consist of one of more of the following: (i) plutonium; (ii) uranium with an enrichment of 20% and above, taken account of by multiplying its weight by its enrichment; and (iii) uranium with an enrichment below 20% and above that of natural uranium, taken account of by multiplying its weight by 5 times the square of its enrichment; (b) 10 metric tons in total of natural uranium and depleted uranium with an enrichment above 0.5%; (c) 20 metric tons of depleted uranium with an enrichment of 0.5% or below; and (d) 20 metric tons of thorium; or such greater amounts as may be specified by the Board of Governors for uniform application.

Fateme Fazel was a Graduate Professional in the Middle East WMD-Free Zone project. Previously, she interned at the Tehran Peace Museum, an Iranian NGO whose mission revolves around combatting weapons of mass destruction, and worked for several Iranian research institutions in fields such as data governance, health law and migration studies. Fateme holds a Bachelor of Arts in Law from Tehran University and a Master’s in International Law from Shahid Beheshti University, Iran