The platonic ideal of space governance is a trifecta of security, safety and sustainability: distinct concepts characterized by both overlaps and complementarities. Crucially, effective space governance requires all countries – regardless of their indigenous spacefaring capabilities – to be engaged in ongoing discussions, and to signal their buy-in through support for existing governance mechanisms and ratification of space treaties. To that end, attention should be paid on the increasingly diverse cohort of countries busy formulating national space policies, strategies, legislation, as well as launching and operating their first satellites and engaging in other space activities.

This commentary will look at the benefits of ratification of international space treaties for States Parties and briefly highlight under-explored opportunities within the existing space governance toolbox. Drawing on primary resources via open-source research as part of the author’s work on UNIDIR’s Space Security Portal, the commentary focuses on the Southeast Asian region – specifically, on the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as a case study. This builds on earlier UNIDIR regionally focused activities in Africa, GRULAC and Small Island States, among other regions.

ASEAN Member States in space

Member States of ASEAN demonstrate a growing interest in space-related activities for peaceful purposes, increasingly to the attention of private sector actors. Across international fora, statements are regularly and consistently delivered on behalf of ASEAN Member States, reiterating the right to the peaceful use and exploration of outer space, for the benefit of all humankind.

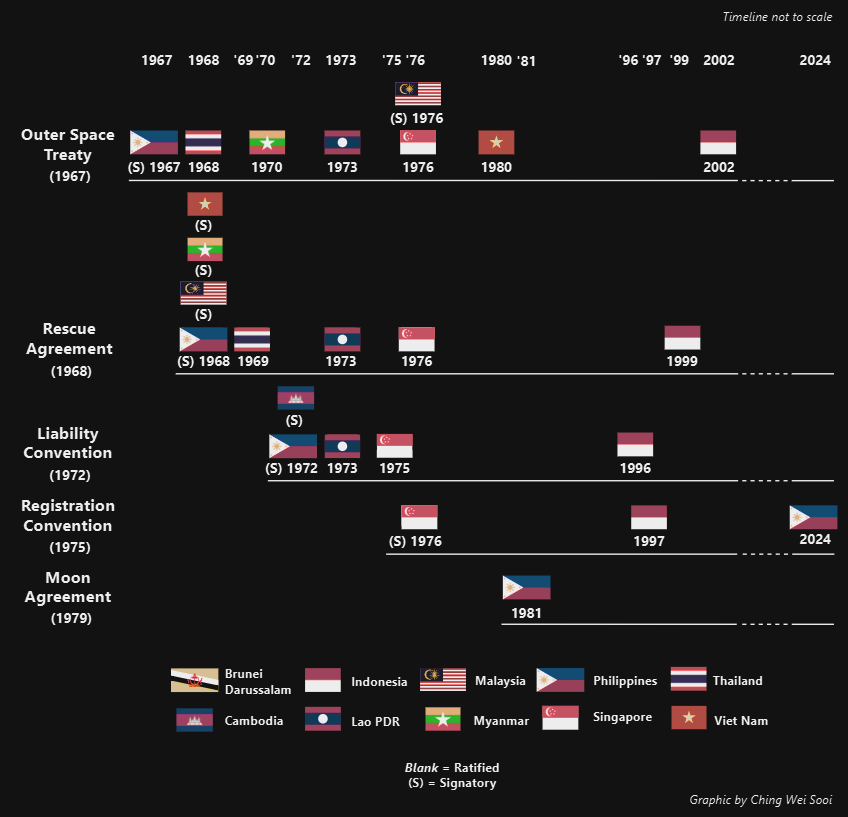

As such, the region is an illustrative mosaic of how countries take steps towards becoming more established actors in space. Within this group, there are countries that have ratified some or most space treaties (with a majority being members of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, and others having requested to participate as observers); countries that have signed but not ratified space treaties; and countries that are not party to most or any space treaties. A timeline of ratification and signatories is provided in Figure 1.

While ratification binds a State Party to a treaty, a “signatory State” status indicates the desire to continue the treaty implementation process; to proceed to ratification, acceptance or approval, and to avoid acts contrary to the object and purpose of the treaty. As Figure 1 illustrates, a number of countries are party to several treaties. For example, Indonesia has ratified four of the five space treaties. The Philippines has expressed intentions to ratify the Outer Space Treaty (OST), Liability Convention and Rescue Agreement and seems set to become party to all five space treaties, joining the ranks of only 15 other countries worldwide to have ratified all five. Other examples of progress include Malaysia’s ongoing work to become party to the OST and Rescue Agreement.

The ratification of treaties and the development of domestic policies and legislation can be a long, difficult and resource-intensive process. Nonetheless, as indicated by Figure 1, Southeast Asia is witnessing a growing amount of domestic space legislation and guidelines. For example:

- The Philippines’ Space Act is a robust example of domestic efforts reinforcing international treaties, having established a policy “to ensure that the Philippines abides by the various international space treaties and principles promulgated by the United Nations”. As such, the Act directly references the OST, Registration Convention and Liability Convention.

- Singapore’s Guidelines for Singapore-Related Space Activities covers the registration of space objects. It is also worth highlighting that Singapore’s Guidelines goes beyond focusing on treaty obligations in promoting space sustainability through “international requirements, guidelines, standards and best practices” such as the Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines and Long-Term Sustainability Guidelines.

- Malaysia’s Space Board Act 2022 covers the registration of space objects and creates a register of space objects. Notably, the legislation also has provisions which go further than similar provisions found in the OST: the Space Board Act prohibits the placement, installation, launch, testing or operation of weapons of mass destruction in space; and also prohibits the establishment of military bases, installations and fortifications in space. In contrast, the OST specifically prohibits the placement of weapons of mass destruction in orbit and their stationing in outer space, without addressing their launch, testing or operation. Regarding military bases, installations and fortifications, the OST forbids their installation on celestial bodies rather than in outer space more generally.

Unilateral steps to take on more expansive laws and policies can be beneficial for the international regime. This may be one way to overcome impasses at the international level and serve as a trust and confidence-building measure. If this were repeated by more countries, these practices could eventually become recognized as international customary law.

These three examples show how domestic instruments could serve as stepping stones towards ratification by encouraging and expediating future decisions to become a Party to relevant treaties. On top of being an opportunity for knowledge-sharing, domestic mechanisms can be designed with provisions, which in essence, implement treaty obligations. Moreover, contributions such as these to the global space governance landscape can help improve security, safety and sustainability overall and serve as useful examples to other countries, including at the regional level where regional dialogue in Southeast Asia and beyond is already shaping discourse around space security.

ASEAN plays multiple roles for Southeast Asia in space. The ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), established in 1994, serves to foster dialogue, consultation and confidence-building on political and security issues relevant to the Asia-Pacific, and includes a geographically diverse total of 27 members. There have been three ARF Track I workshops on space security to date, hosted by Hoi An in 2012, Tokyo in 2014 and Beijing in 2015.

Separate to the ARF, ASEAN established a Sub-Committee on Space Technology and Applications (SCOSA) in 1999. SCOSA serves as an avenue for projects, activities and programmes such as knowledge-sharing workshops with international partners outside of Southeast Asia. The current objectives of SCOSA were determined in 2016 and run until 2025. It will be interesting to monitor the objectives that emerge subsequently.

Lastly, it should also be noted that the Asia Pacific Regional Space Agency Forum and the Asia Pacific Space Cooperation Organisation regularly organise activities more broadly for the Asia-Pacific region.

Doubling down on space governance

All countries have a role to play in preventing space governance from fragmenting, and there is no need to reinvent the wheel. As important as it is to make headway into dealing with new challenges, risks and threats, it is also important to buy into and strengthen existing governance mechanisms. After all, arguably the current toolbox has not been fully utilized by States Parties. While it is beyond the scope of the commentary to explore this topic in greater depth, some preliminary examples follow.

With respect to the OST:

- Article IX provides a consultative mechanism between State Parties. The article has latent potential to address issues related to harmful interference in space-related activities, improve transparency in space and benefit relations through demonstrations of trust and cooperation.

- Article XI calls for the sharing and exchange information “to the greatest extent feasible and practicable, of the nature, conduct, locations and results” of activities conducted in outer space. This could reduce the risk of miscommunication, misperception and misunderstandings.

- And as lunar activities are set to increase, article XII opens the door to “all stations, installations, equipment and space vehicles on the moon and other celestial bodies… to representatives of other states parties to the Treaty on a basis of reciprocity”.

Regarding the Registration Convention, increasing compliance and the provision of information beyond what is minimally required would improve this treaty’s key role in transparency and confidence building. Additionally, article VI of the Registration Convention creates a mechanism for requests for information which could also aid in providing greater transparency in space-related activities.

Information requests and consultations, if utilized in good faith, provide opportunities for countries to explain the rationale behind space activities that are of interest to others and could aid in the identification of space objects and mitigate concerns over their purpose and intent. While providing greater information may generate national security concerns, in an increasingly congesting and contested space environment, the benefits of greater transparency could enable countries to strike a balance in accounting for such concerns.

Moving beyond treaties, countries are afforded an assortment of initiatives to strengthen existing frameworks for space security governance. States not yet party to the Registration Convention are still able to provide information on their space objects through A/RES/1721(XVI) B. For instance, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines and the Lao People’s Democratic Republic have registered space objects using this approach. Also of relevance is A/RES/62/101 which recommends methods to strengthen the Registration Convention.

Finally, the reports of the 2013 Group of Governmental Experts on Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures in Outer Space Activities and 2023 UN Disarmament Commission Working Group II provide a rich selection of transparency and confidence building measures. Instruments such as the Long-Term Sustainability Guidelines (A/74/20, para 163 and Annex II) and Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines remain available for further implementation as well.

A Path Forward

An increasing number of countries are charting their journey into the stars. Their ratification of and adherence to space treaties; development of domestic instruments such as legislation and guidelines; and use of existing mechanisms could create a complementary, global patchwork with which to strengthen space governance.

This would aid in establishing State practice under international law, and the broader acceptance of general principles of law makes it more likely that they could eventually become customary international law. A tapestry of common understanding is ready to be weaved, improving transparency and (re)building trust and confidence.

The five space treaties, negotiated during the Cold War, remain as enduring symbols of how positive, constructive engagement is possible amidst tension and rivalry. The benefits from the treaties continue to be accrued to this day. While important, forward-looking discussions continue to work on addressing issues relevant to space security, safety and sustainability, the international space community – regardless of their degree of spacefaring prowess – should not lose sight of what it has at present, and the possibilities already available.

Ching Wei Sooi was a Graduate Professional with UNIDIR’s Space Security and WMD Programmes and is currently pursuing an MA in International Peace and Security at King’s College London. Previously, he was an intern with the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs under the Office of the Director. The author would like to thank Almudena Azcárate Ortega, Sarah Erickson and James Revill for their invaluable advice and support on this commentary.